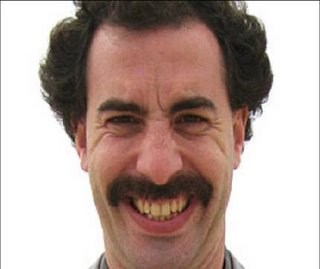

Although I hardly ever have time to read it cover to cover before the next issue shows up, The New Yorker may very well be the grand dame of the literary world. Nevertheless, not every word of its extensive essays is automatically substantiated by the overall prestige of the publication. Anthony Lane's Borat review certainly shouldn't be taken as gospel. There are problems from the very first (very lengthy) opening paragraph, and they continue all the way through:

Well, here goes: First of all, if Lane every bothered to watch Da Ali G Show, he'd know that the title character wasn't invented before Borat-- or even Bruno, the third character on the show and the subject of Baron Cohen's next feature film, according to the trades. Ali G is the most memorable character because he's the most immediately likable, unlike Borat and Bruno, whose respective savagery and homosexuality obviously intimidate certain members of the audience. Second of all, a little biographical research on the fascinating career trajectory Baron Cohen has followed since the days of his thesis on the Black-Jewish Alliance tells you that, if anything, the Borat persona made its showbiz debut before all the other characters (one of his earliest audition tapes featured him performing as an invented Albanian reporter).

Second of all, while Ali G did indeed find a "televised niche," his movie, Ali G Indahouse, was a box office smash in the UK and at least got some air time on HBO, allowing for a cult following and decent DVD sales here in the States. The reason why Borat came to America doesn't have anything to do with whatever "hurt pride" nonesense Lane is trying to explicate; Baron Cohen brought all his characters here simply because he got way too popular in his native country, to the point where even the Queen was puportedly quoting his catchphrases. He was so recognizable that the gimmick of his show didn't work because everybody knew when they were being duped. And anyways, dude, the sore spots are all over the place. Borat could make a fool out of people in Paraguay, if he spoke bad Spanish.

Look, Lane, you're totally entitled to hate on movies if it gets you the badass reputation you seem to relish without fail. But at least do your homework.

Also, if you can bear to read the rest of the piece, you'll notice that Lane just doesn't seem to get the humor. Not one iota. He can't seem to describe what makes this type of performance art so fucking hilarious, and he ends up being condenscending towards Baron Cohen as a result. Which makes him another Borat victim.

And this, of couse, allows me to plug my upcoming review of the movie later this week in The Reeler, where I promise to at least try to sound like I sort of know what I'm rambling about. Dig it.